2 Accessing Newspaper Data in the UK

This chapter outlines the major sources of newspaper data available in the UK.

One important thing to note is that the chapter deals with text only, that is, newspaper data in the form of text derived from the images of the printed pages. The images themselves are important and increasingly the object of research in their own right, but this book doesn’t focus on them. In some of the cases below, but not all, the images can be accessed alongside the derived text. The newspapers described below are generally made available in a format known as METS/ALTO, which will be explained in more detail in Chapter 5.

The guide is aimed as a brief, practical overview. For more detailed information, I highly recommend checking out the Atlas of Digitised Newspapers project, which currently has very detailed information on the digitised newspapers and data for ten collections worldwide, including descriptions of metadata, standards, and API access.

What is Available? In a Nutshell:

Most of the available newspaper data in the UK is based on the collections of the British Library (though other libraries do hold significant collections). This is a huge collection, but getting access to it is not straightforward. In a nutshell:

- If your research is more methods-based or doesn’t necessarily need full coverage, you could use the freely-available, public domain Heritage Made Digital and Living with Machines titles. These are used in the second section of the book as the basis for the coding tutorials.

- If you would like to do analysis on something slightly more representative, you could contact Gale and ask them to supply you with the JISC Historical Newspaper Collection. Hopefully, these titles will be made freely available in the coming years.

- To work with the largest dataset of newspapers, you would need an agreement with a commercial company, Find My Past.

British Library Newspapers - The Physical Collection

The British Library holds about 60 million issues, or 450 million pages of newspapers. They now span over 400 years, but the coverage prior to the nineteenth century is very partial (King 2007). Prior to 1800, the collection has serious gaps, and many issues of many titles have simply not survived. This means that only a fraction of what was published has been preserved or collected, and only a fraction of that which has been collected has been digitised.

It’s actually surprisingly difficult to know exactly what has been digitised, but a rough count is possible, using the ‘newspaper year’ as a unit. This is all the issues for one title, for one year. Its not perfect, because a newspaper-year of a weekly looks the same as a newspaper-year for a daily, but it’s an easy unit to count. There are currently about 40,000 newspaper-years on the British Newspaper Archive. The entire collection of British and Irish Newspapers is probably about 350,000 newspaper-years.

It’s all very well being able to access the content, but for the purposes of the kind of things we’d like to do, access to the data is needed. The following are the main British Library digitised newspaper sources. The following is organised into two time periods: before and after 1800.

Pre-1800

Newspapers before 1800 are treated different to later ones and even constitute a different collection in the British Library. First of all, the collection of pre-1800 newspapers is much smaller and much less complete. This is partially because the British Library did not collect newspapers systematically until well into the nineteenth century. Therefore, even though they are out of copyright, there are no large-scale, centralised collection of early newspapers and newsbooks (their precursors).

Close to the entirety of the surviving collection of newspapers (called newsbooks from the seventeenth century, by and large) has been digitised and made available online, through resources such as EEBO, JISC Historical Texts, and Gale Primary Sources. Many universities and libraries will provide access to these resources, allowing you to browse, search and read through the texts.

Getting access to the underlying text data is less straightforward, however. Where there is OCR data of these titles, the age and quality of these texts mean it is not particularly suited to data analysis. Secondly, the images and texts themselves are mostly behind paywalls and there is no easy provision for bulk downloading of either. Two sources of newspapers for those interested in pre-1800 are worth mentioning: 1) the Burney Collection and 2) the Thomason Newsbook Collection.

The Thomason Newsbook Collection

The Thomason Tracts are a collection of pamphlets, periodicals and broadsides held at the British Library. Part of this are approximately 7,200 serials (or periodicals). These were digitised from microfilm scans in the 1990s, and made available online through the resource Early English Books Online (EEBO). A separate project the Text Creation Partnership (EEBO-TCP), created double-keyed transcriptions of many EEBO texts, but, sadly, not including serials (though it does include news pamphlets). These transcribed texts, in TEI-encoded format, are freely available online.

Some smaller corpora of Thomason newsbooks have been created. These include the Lancaster Newsbook Corpus, a collection of several hundred manually-transcribed serials from the 1650s, and ‘George Thomason’s Newsbooks’, which is a corpus of all newsbooks printed in the year 1649, as well as the entire run of a single title, Mercurius Politicus. Neither of these may be suited to the kind of large-scale analysis proposed in this book, but they may anyway be of interest.

Burney Collection

The Burney Collection contains about one million pages, from the very earliest newspapers in the seventeenth century to the beginning of the nineteenth, collected by Rev. Charles Burney in the eighteenth century, and purchased by the Library in 1818(Prescott 2018). It’s actually a mixture of both Burney’s own collection and material inserted afterwards. It was microfilmed in its entirety in the 1970s and imaged in the 90s but because of technological restrictions it wasn’t until 2007 when, with Gale, the British Library released the Burney Collection as a digital resource.

It’s not generally available as a data download, but the raw OCR would be of limited use anyway. Older OCR for early modern print is not very good, and it was certainly worse ten years ago when the collection was processed. The accuracy of the OCR has been measured, and Prescott (2018) found that the ocr for the Burney newspapers offered character accuracy of 75.6% and word accuracy of 65%.

However, this is still a useful collection for browsing and keyword searching, which can usually be accessed through an institutional subscription to Gale, packaged as the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

After 1800

The British Library newspapers after 1800 is a much larger collection, and from the middle of the century, is quite comprehensive. Some more on the history of the collection is can be found in Chapter 4. A number of resources make digital surrogates of these newspapers available.

JISC Newspaper digitisation projects

Most of the academic projects in the UK which have used newspaper data, from the Political Meetings Mapper, to the Victorian Meme Machine have used the British Library’s 19th Century Newspapers collection, published by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC).

What is available?

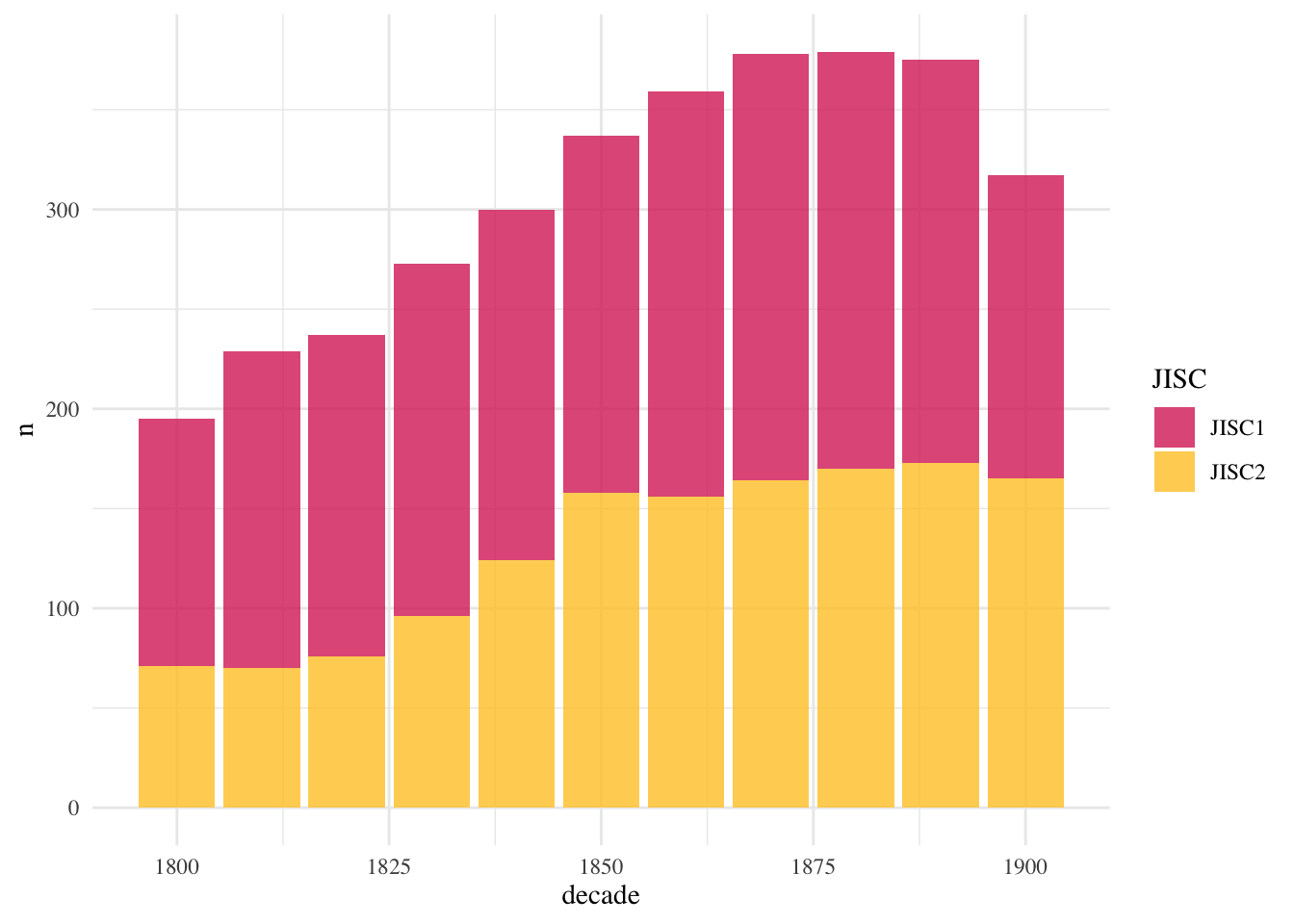

JISC is mostly a collection of large regional titles from across the nineteenth century, which were picked for a variety of reasons, outlined below. There are titles from many major UK towns and cities. Figure Figure 2.1 charts the number of titles per decade: the coverage of the nineteenth century is more weighted towards the end, but this also reflects the increase in the newspaper collection as a whole.

History

The JISC newspaper digitisation program began in 2004, when The British Library received two million pounds from the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) to complete a newspaper digitisation project. A plan was made to digitise up to two million pages, across 49 titles.(King 2007) A second phase of the project digitised a further 22 titles.(Shaw 2007, 2005)

Coverage

The titles cover England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, and it should be noted that the latter is underrepresented although it was obviously an integral part of the United Kingdom at the time of the publication of these newspapers - something that’s often overlooked in projects using the JISC data. They cover about 40 cities @ref(fig:jisc-points), and are spread across 24 counties within Great Britain @ref(fig:jisc-map), plus Dublin and Belfast. To quote the then curator of the newspapers, Ed King:

The forty-eight titles chosen represent a very large cross-section of 19th century press and publishing history. Three principles guided the work of the selection panel: firstly, that newspapers from all over the UK would be represented in the database; in practice, this meant selecting a significant regional or city title, from a large number of potential candidate titles. Secondly, the whole of the nineteenth century would be covered; and thirdly, that, once a newspaper title was selected, all of the issues available at the British Library would be digitised. To maximise content, only the last timed edition was digitised. No variant editions were included. Thirdly, once a newspaper was selected, all of its run of issue would be digitised.(King 2008)

Further information on the selection process comes from Jane Shaw, who wrote in 2007 that:

The academic panel made their selection using the following eligibility criteria:

To ensure that complete runs of newspapers are scanned

To have the most complete date range, 1800-1900, covered by the titles selected

To have the greatest UK-wide coverage as possible To include the specialist area of Chartism (many of which are short runs)

To consider the coverage of the title: e.g., the London area; a large urban area (e.g., Birmingham); a larger regional/rural area To consider the numbers printed - a large circulation

The paper was successful in its time via its sales

To consider the different editions for dailies and weeklies and their importance for article inclusion or exclusion To consider special content, e.g., the newspaper espoused a certain political viewpoint (radical/conservative)

The paper was influential via its editorials. (Shaw 2007)

The result was a heavily curated collection, which has been scrutinised by historians (Fyfe 2016 for example).

Recently, the Living with Machines project has done the most thorough assessment of the specific biases of the collection. Doing what has been termed an ‘environmental scan’ of the newspaper collection, and linking it to press directories containing information on geographic coverage, political leanings, and price, that team has shown that it had specific biases in some areas (Beelen et al. 2022).

This is all covered in lots of detail elsewhere, including some really interesting critiques of the access and so forth. Smits (2016) and Mussell (2014) both include some discussion and critique of the British Library Newspaper Collection.

Regardless of its representativeness, it only contains a tiny fraction of the newspaper collection, and by being relevant and restricted to ‘important’ titles, it does of course miss other voices. For example, much of the Library’s collection consists of short runs, and much of it has not been microfilmed, which means it won’t have been selected for digitisation. This means that 2019 digitisation selection policies are indirectly greatly influenced by microfilm selection policies of earlier decades. Subsequent digitisation projects are trying to rectify these imbalances.

The map below is interactive and shows the locations of the JISC 1 and 2 collections. Clicking on a point will bring up a list of the newspapers digitised in that place; clicking on these links will bring you to the British Library’s catalogue page for that title.

Interactive map of the JISC 1 & 2 digitised collections

Access

Currently researchers access this either through Gale, or through the British Library as an external researcher. Many researchers have requested access to the collection through Gale, which they will apparently do in exchange for a ‘cost recovery’ fee. These files were digitised using a specific format, and the text from them can be extracted using a tool developed by Living with Machines, which I’ll explore in a future chapter.

British Newspaper Archive

Most of the British Library’s digitised newspaper collection is available on the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). The BNA is a commercial product run by a family history company called FindMyPast. FindMyPast is now responsible for digitising large amounts of the Library’s newspapers, mostly through microfilm. As such, they have a very different focus to the JISC digitisation projects. The BNA is constantly growing, and it already dwarfs the JISC projects by number of pages: the BNA currently hosts nearly 70 million pages, against the 3 million or so of the two JISC projects. A recent project, thanks to an agreement between the supplier and the British Library, means that one million pages per year are being made freely available to read through the platform, if you register for a free account.

Coverage

The BNA collection is very large, and is particularly focused on local newspapers. At time of writing, the BNA website (linked above) contains over 68 million pages, with more added on a weekly basis.

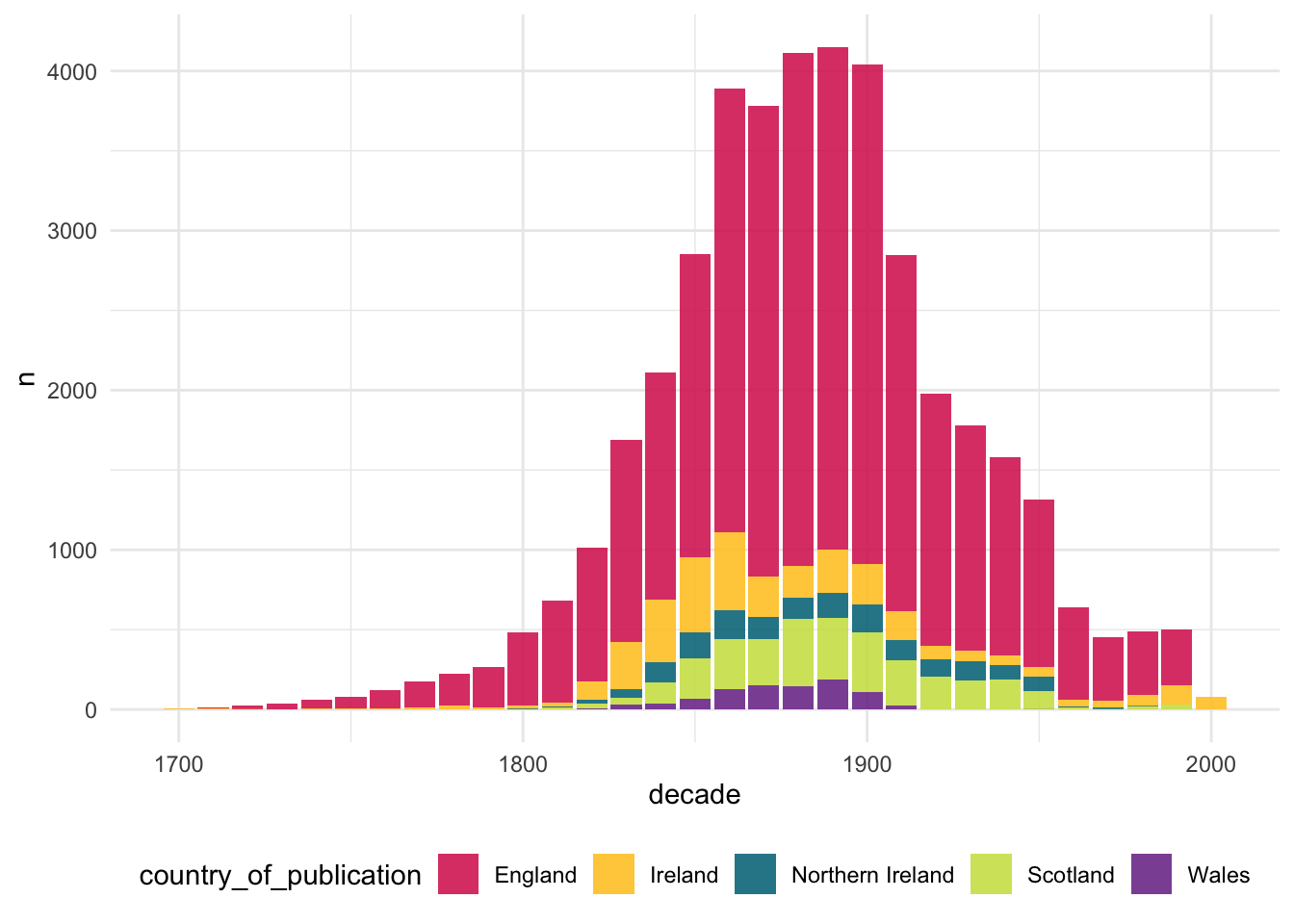

The titles it contains span the entire nineteenth century, peaking from 1850 - 1900. Figure Figure 2.2 charts the volume of material on the British Newspaper Archive, per year. It is derived from the metadata rather than the actual volume of data. The ‘unit’ is the newspaper year, meaning each year of a newspaper’s run is counted as a single data point. It doesn’t account for weekly versus daily titles, or the number of pages, but it gives an idea of the temporal shape of the coverage.

Geographically, the BNA collection is also widely spread. The most important distinction between it and JISC is that the BNA covers a much wider range of smaller, local titles. Figure Figure 2.3 maps all the titles digitised and available on the British Newspaper Archive. In this case, clicking a link will bring you to the page for that title on the resource. You’ll need a subscription (or a free account if they happen to be free-to-view titles) to view it in its entirety.

The map is not complete - titles from Ireland are not shown at the moment because of an issue with the metadata, but will be added in a later update. However the map gives a good sense of the geographic coverage, which is particularly clustered in parts of the Midlands and North, as well as London. Many smaller villages and towns are represented. Coverage in Wales is still patchy, but most big population centres are represented.

Access

The BNA’s primary focus is on providing search access to individual researchers. Sadly, there is little provision made for data access, or even institutional subscriptions for researchers. There are some exceptions: the Bristol N-Gram and named entity datasets project used the BNA data, processing the top phrases and words from about 16 million pages. The collection has tripled in size since then: it’s likely that were it to be run again the results would be different.

The Living with Machines project negotiated a full data transfer directly from Find My Past (the owners of the British Newspaper Archive) for the first time. The story of this is written in some detail in the book Collaborative Historical Research in the Age of Big Data (Ahnert et al. 2023). In a nutshell, because of copyright issues, the project had to deal directly with Find My Past, and there were a set of detailed restrictions on what could be done with the data, such as having to keep it in secure storage, and delete it after two years.

That is all to say that working with ‘all’ the UK’s available digitised newspaper data is probably not feasible for most individual researchers or even small or medium-sized research projects, at the present time. While hopefully this will change in the future, what it means for now is that most data-driven historical work carried out on newspapers has used the JISC data, rather than the much larger BNA collection, because of relative ease-of-access.

British Library Open Research Repository (bl.iro.bl.uk)

However, there is some positive news in accessing UK newspaper data, thanks to a new resource which has become available in the last couple of years: the Shared Research Repository, a resource maintained by the British Library. Newspaper digitisation projects carried out internally by the British Library do not have the same copyright or commercial restrictions as JISC and the BNA, meaning in theory the data from them can be opely shared with no license restrictions. Two recent projects, Living with Machines and Heritage Made Digital, have carried out digitisation in this way, and so the data can be much more easily and openly shared. It is still a tiny collection in comparison to the entire BNA, but it is a step in the right direction.

The BL open repository is a centralised repository for all sorts of research outputs and data, and the Library has been using it as a storage space for newspaper data from various newspaper digitisation projects. The text data (not the images) have been made freely available, with no license restrictions, meaning they can be used for any purpose whatsoever.

Coverage

As of publication, a total of 57 titles, or 437 ‘newspaper years’ are currently available.

These titles currently come from two sources:

The Living with Machines project

Heritage Made Digital

Because the information on the motivations behind these projects is somewhat new, more transparent, and easier to access, I’ll explain them in a bit more detail.

Living with Machines

The Living with Machines project, a collaboration between the Alan Turing Institute and the British Library (as well as other partners), has digitised and made available a new selection of newspapers. According to that project, the aim of the digitisation was research-led rather than curatorial, meaning they chose their titles according to flexible research needs. According to the project, the key aims for the digitisation were to respond to specific research questions, and to rebalance the bias in the existing newspaper corpus (Tolfo et al. 2022). The eventual selections were a mix of research interests and ‘practical factors’.

To help with choosing the most useful and optimal set of newspapers to digitise with limited resources, the team developed a number of tools, including a user interface called Press Picker, as well as digitising a set of press directories, which hold information on the newspapers which could then be used in making choices.

The project’s historical research interest focused on industrialisation and its impact, and as a result many of the titles digitised are specifically related to that subject, for example by the topic or area of coverage of the newspaper.

Heritage Made Digital

Heritage Made Digital was a project within the British Library to digitise up to 1.3 million pages of 19th century newspapers. It has a specific curatorial focus: it picked titles which are completely out of copyright, which means that they all finished publication before 1879. It also had preservation aims: because of this, it chose titles which were not on microfilm, and were also in poor or unfit condition. Newspaper volumes in unfit condition cannot be called up by readers: this meant that if a volume is not microfilmed and is in this state, it can’t be read by anyone.

The other curatorial goal was to focus on ‘national’ titles. In practice this meant choosing titles printed in London, but without a specific London focus. The JISC digitisation projects focused on regional titles, then local, and all the ‘big’ nationals like the Times or the Manchester Guardian have been digitised by their current owners. This means that a group of historically important titles may have fallen through the cracks, and this projects is digitising some of those.1

As can be seen in Figure Figure 2.4, the years digitised so far cover most of the century, with the Living with Machines titles focused on the second half, and Heritage Made Digital slightly earlier.

Taken together, the collection spans much of the UK, with an emphasis on London and industrial areas, because of the focus of the projects.

This map in Figure Figure 2.5 displays them. A few are currently missing from the map because the relevant ID numbers to link them to the title list and ultimately, geographic coordinates, were not found. The links in the pop-up take you to the download page for that title on the Open Research Repository.

Access

The good news is that as these newspapers are deemed out of copyright, the text data can be made freely downloadable. Currently the first batch of newspapers, in METS/ALTO format, are available on the British Library’s Open Repository. They have a CC-0 licence, which means they can be used for any purpose whatsoever. The code examples in the following chapters will use this data, and chapter six will show you how to download the titles using a bulk downloader, instead of going through them one-by-one.

The titles are primarily available as individual downloads through the web interface of the repository. Downloading them is as simple as clicking a link to a .zip file. The easiest way to find all of them is to use the collections organisational system of the repository. The collection British Library News Datasets contains a number of newspaper datasets, including metadata and newspapers. The newspapers themselves are contained with the sub-collection Newspapers. If you click on this second link, you’ll see a list of datasets. Each dataset corresponds to a single title (actually, often a group of titles if they changed name or merged). Clicking on a title will display a page containing links to .zip files, one for each year of the title. Note that there may be multiple pages.

Downloading the data one year of a title at a time can be a time-consuming process. In (Chapter 8), I’ll demonstrate some methods for downloading titles in bulk.

Other data sources

As a final note, there are also a number of really useful metadata files available through the British Library research repository. Firstly, two title-level lists of all British and Irish Newspapers held by the library: one for Britain and Ireland here, and an updated, world-wide one, here. A later chapter Chapter 7 describes these in some more detail.

Most recently, the Living with Machines project has published two digitised press directories, available here and here, plus a dataset of extracted structured data. All of these are have a Public Domain licence.

Recommended Reading

Beelen, Kaspar, Jon Lawrence, Daniel C S Wilson, and David Beavan. “Bias and Representativeness in Digitized Newspaper Collections: Introducing the Environmental Scan.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 38, no. 1 (April 3, 2023): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqac037.

Fyfe, Paul. “An Archaeology of Victorian Newspapers.” Victorian Periodicals Review 49, no. 4 (2016): 546–77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26166577.

The term national is debatable, but it’s been used to try and distinguish from titles which clearly had a focus on one region. Even this is difficult: regionals would have often had a national focus, and were in any case reprinting many national stories. But their audience would have been primarily in a limited geographical area, unlike many London-based titles, which were printed and sent out across the country, first by train, then the stories themselves by telegraph.↩︎